Bearing Much Fruit

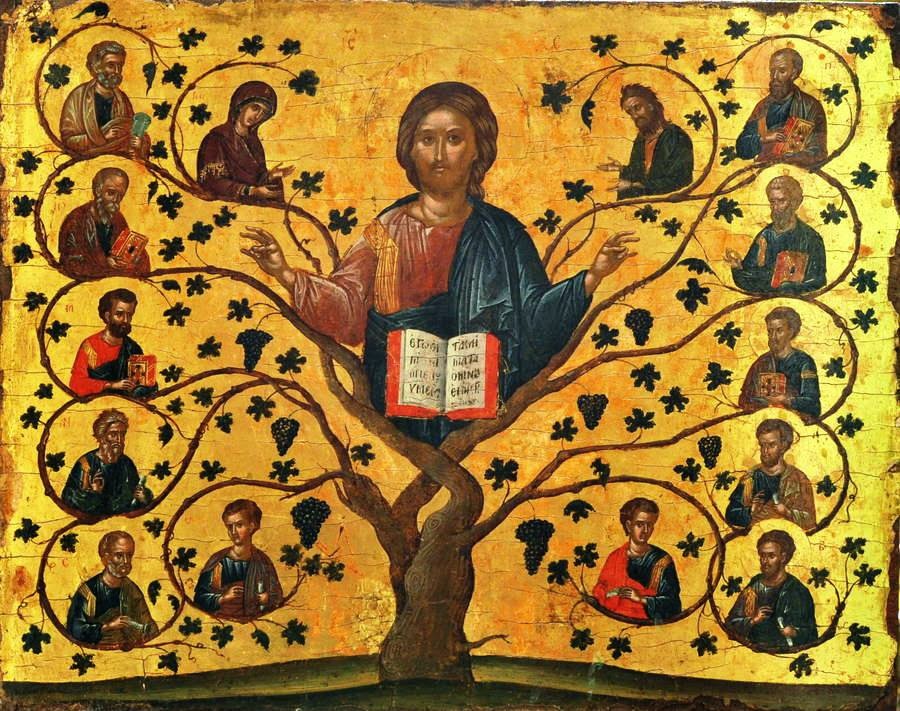

Christ the True Vine

COMMENT:

The Gospel of Sunday of 5th Week of Easter is repeated on

Wednesday of the week.

Gospel John 15:1-8, "I am the true vine, and my Father is the vinedresser.

...."

For the Sunday Homily, we are indebted to Redemptorist Publication 'The Living Word, quoting Karl Rahner, "The Christian of the future will either be a 'mystic' ... or ... will cease to be anything at all."

For the Tuesday Patristic Reading, John by Saint Cyril of Alexandria, bishop

(Lib. 10, 2: PG 74, 331-334),I am the vine, you are the branches

"Make

your home in me, as I make mine in you."

Illustration

Karl

Rahner SJ, one of the great theologians of the last century, wrote many books in

which he tried to make sense of the Catholic faith for his contemporaries. That's

what a theologian has to do. Towards the end of his life he wrote an influential

essay on the future of the Christian faith. It began with this provocative

statement: "The Christian of the future will either be a 'mystic' ... or ...

will cease to be anything at all."

Did he

mean that we must all have visions like St Teresa of Avila? Karl Rahner thought

that the old Catholic culture that he had known as a boy was fast disappearing,

eroded by an increasingly secular world. It meant that the average Christian

could not depend on a Christian culture that everyone took for granted. So he

thought that unless Christians had a deep and personal experience of God they

would not be able to keep up the practice of their faith. That is all he meant by

saying that each person needed to be a mystic. No matter how big the institutional

Church seems to be, if its members do not have in them the life blood of a

personal encounter with God, then it will wither away.

Gospel Teaching

Jesus

took for granted that his Jewish faith needed laws and institutions like the Temple

if it was going to transmit its message to the next generation. And so he knew

that his Church must be built on the rock of Peter; then God would preserve it

from all its enemies. But in today's Gospel, he tells his disciples at the Last

Supper that if they are to survive they must remain close to him. He takes the

image of the vineyard, which was used

to represent Israel in the Old Testament, and in a sense identifies himself with

it by saying: "I am the true vine,

and my Father is the vinedresser."

If

the disciples are to survive then they must be branches of Jesus, the vine. And just as a vine is pruned to make it more fruitful,

the disciples will also grow by being tested in their faith. Jesus tells them to

remain close to him and have the living sap flowing in their branches, or else

they will shrivel up. He insists that at the heart of their faith there is this

close personal relationship with him: "Make your home in me, as I make

mine in you." As they are united in Christ so they will be united through

him to the Father. But this experience is not just for special members of the Church,

like the apostles. The Spirit is given to everyone. All are called to have this

"mystic" experience of being so close to Christ in their daily life

that they produce good fruit.

Application

It is easy to get carried along by externals. The Church is essential

to our faith. We cannot

say, as some do,

that we

want Jesus but

not the Church. In the Creed

we affirm our belief in Jesus Christ

and also

in "one,

holy, catholic and apostolic Church". The institutional Church is a key part of

our faith,

but there

is always the

danger of just going through the motions and dying on the

vine. The

institution will shrivel unless

its members

have the sap of the living Christ flowing through

them.

As Karl Rahner pointed out, it is much more

difficult now to be carried along by other

people's faith in

a society

that is both secular

and often hostile

to our beliefs. How can we produce the fruit that will show that Christ's

Church is alive

and well? We do not need to be

mystics like some of the great saints,

but to make sure our practice of the faith, whether it is going

to Mass or saying our prayers, is firmly based on a close personal relationship with Jesus. We don't at first have to do anything but rather to be at peace in

his presence,

to allow

him to dwell in

us: Then

we can share a deep communion with him as we receive his

body and blood in the Eucharist. If we change

the image from sap, we could say that his real presence in his

blood gives us new life. If we do have

this close relationship of the branch to the

"true vine", then it will produce good fruits

especially in the

way we love God and

one another.

Summary

1.

We are all called to have a

personal experience of God.

2.

The institutional Church is necessary but its members must be branches of Christ, the vine;

we will only be alive

if we dwell in him and he in us.

3.

Our faith is to be inspired by this personal close relationship with Christ so that

the Church will

produce good

fruits. +++++++++++

iBreviary

Tuesday, 5 May 2015

Tuesday of the Fifth Week of Easter

Type: Weekday - Time: Easter

SECOND READING

From a commentary on the gospel of John by Saint Cyril of Alexandria, bishop

(Lib. 10, 2: PG 74, 331-334)

I am the vine, you are the branches

The Lord calls himself the vine and those united to him branches in order to teach us how much we shall benefit from our union with him, and how important it is for us to remain in his love. By receiving the Holy Spirit, who is the bond of union between us and Christ our Savior, those who are joined to him, as branches are to a vine, share in his own nature.

On the part of those who come to the vine, their union with him depends upon a deliberate act of the will; on his part, the union is effected by grace. Because we had good will, we made the act of faith that brought us to Christ, and received from him the dignity of adoptive sonship that made us his own kinsmen, according to the words of Saint Paul: He who is joined to the Lord is one spirit with him.

The prophet Isaiah calls Christ the foundation, because it is upon him that we as living and spiritual stones are built into a holy priesthood to be a dwelling place for God in the Spirit. Upon no other foundation than Christ can this temple be built. Here Christ is teaching the same truth by calling himself the vine, since the vine is the parent of its branches, and provides their nourishment.

From Christ and in Christ, we have been reborn through the Spirit in order to bear the fruit of life; not the fruit of our old, sinful life but the fruit of a new life founded upon our faith in him and our love for him. Like branches growing from a vine, we now draw our life from Christ, and we cling to his holy commandment in order to preserve this life. Eager to safeguard the blessing of our noble birth, we are careful not to grieve the Holy Spirit who dwells in us, and who makes us aware of God’s presence in us.

Let the wisdom of John teach us how we live in Christ and Christ lives in us: The proof that we are living in him and he is living in us is that he has given us a share in his Spirit. Just as the trunk of the vine gives its own natural properties to each of its branches, so, by bestowing on them the Holy Spirit, the Word of God, the only-begotten Son of the Father, gives Christians a certain kinship with himself and with God the Father because they have been united to him by faith and determination to do his will in all things. He helps them to grow in love and reverence for God, and teaches them to discern right from wrong and to act with integrity.

RESPONSORY

John 15:4, 16

Live in me as I live in you.

– Just as a branch cannot bear fruit of itself apart from the vine,

so you cannot bear fruit unless you live on in me, alleluia.

I chose you to go out and bear fruit,

a fruit that will last.

– Just as a branch cannot bear fruit of itself apart from the vine,

so you cannot bear fruit unless you live on in me, alleluia.

CONCLUDING PRAYER

Let us pray.

Father,

you restored your people to eternal life

by raising Christ your Son from death.

Make our faith strong and our hope sure.

May we never doubt that you will fulfill

the promises you have made.

Grant this through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son,

who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, for ever and ever.

– Amen.

From a commentary on the gospel of John by Saint Cyril of Alexandria, bishop

(Lib. 10, 2: PG 74, 331-334)

I am the vine, you are the branches

The Lord calls himself the vine and those united to him branches in order to teach us how much we shall benefit from our union with him, and how important it is for us to remain in his love. By receiving the Holy Spirit, who is the bond of union between us and Christ our Savior, those who are joined to him, as branches are to a vine, share in his own nature.

On the part of those who come to the vine, their union with him depends upon a deliberate act of the will; on his part, the union is effected by grace. Because we had good will, we made the act of faith that brought us to Christ, and received from him the dignity of adoptive sonship that made us his own kinsmen, according to the words of Saint Paul: He who is joined to the Lord is one spirit with him.

The prophet Isaiah calls Christ the foundation, because it is upon him that we as living and spiritual stones are built into a holy priesthood to be a dwelling place for God in the Spirit. Upon no other foundation than Christ can this temple be built. Here Christ is teaching the same truth by calling himself the vine, since the vine is the parent of its branches, and provides their nourishment.

From Christ and in Christ, we have been reborn through the Spirit in order to bear the fruit of life; not the fruit of our old, sinful life but the fruit of a new life founded upon our faith in him and our love for him. Like branches growing from a vine, we now draw our life from Christ, and we cling to his holy commandment in order to preserve this life. Eager to safeguard the blessing of our noble birth, we are careful not to grieve the Holy Spirit who dwells in us, and who makes us aware of God’s presence in us.

Let the wisdom of John teach us how we live in Christ and Christ lives in us: The proof that we are living in him and he is living in us is that he has given us a share in his Spirit. Just as the trunk of the vine gives its own natural properties to each of its branches, so, by bestowing on them the Holy Spirit, the Word of God, the only-begotten Son of the Father, gives Christians a certain kinship with himself and with God the Father because they have been united to him by faith and determination to do his will in all things. He helps them to grow in love and reverence for God, and teaches them to discern right from wrong and to act with integrity.

RESPONSORY

John 15:4, 16

Live in me as I live in you.

– Just as a branch cannot bear fruit of itself apart from the vine,

so you cannot bear fruit unless you live on in me, alleluia.

I chose you to go out and bear fruit,

a fruit that will last.

– Just as a branch cannot bear fruit of itself apart from the vine,

so you cannot bear fruit unless you live on in me, alleluia.

CONCLUDING PRAYER

Let us pray.

Father,

you restored your people to eternal life

by raising Christ your Son from death.

Make our faith strong and our hope sure.

May we never doubt that you will fulfill

the promises you have made.

Grant this through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son,

who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, for ever and ever.

– Amen.

This mistaken preference for the modern books and this shyness of the old ones is nowhere more rampant than in theology. Wherever you find a little study circle of Christian laity you can be almost certain that they are studying not St. Luke or St. Paul or St. Augustine or Thomas Aquinas or Hooker or Butler, but M. Berdyaev or M. Maritain or M. Niebuhr or Miss Sayers or even myself.

This mistaken preference for the modern books and this shyness of the old ones is nowhere more rampant than in theology. Wherever you find a little study circle of Christian laity you can be almost certain that they are studying not St. Luke or St. Paul or St. Augustine or Thomas Aquinas or Hooker or Butler, but M. Berdyaev or M. Maritain or M. Niebuhr or Miss Sayers or even myself.